Dec 14, 2009

The Task Is Upon You

Protect our bodies with health nourish our souls with purpose.

Pour knowledge into our minds passion in our hearts.

Expect efficacy and improvement as its currency.

You asked us to reflect.

True desire faces unmet needs with apprehensive tensions

Reflections question reality with rude awakenings sending shivers of concern with Goosebumps of guilt.

What kind of system have we built?

You asked us to envision.

Doubts of broken foundations, shaky pillars, left with bridges that don’t connect.

Our patients we fail to protect.

Commitment and dedication advancing medical knowledge

Measuring its quality brings discrepancy to surface.

Pores sweat, mistaken assumptions composed of salty ignorance

Sincere passions lost through convections leave us cold.

Bold conversations expose realities of a system unjust.

Wake up my good friends, this system has rust.

You asked us to change.

Analyze criticize fundamentals of our fruit.

Bitter a taste of past disgrace transforms into sweet prudent pursuit.

Evolutionary regeneration stimulated by a gravitational force

Demand higher expectations elevate us to greater strengths

Scale up, costs down, aim times three.

Sprint to lead map improvement goals of being complication free.

Our school is one open world a challenge knocks.

Revolutionaries unlock by developing keys that makes us

Better fit to learn, better fit to teach, better fit to reach

Out to our patients, communities, and colleagues.

Declare legitimacy, demand transparency, institute policy.

Strapped with tools ideas for change.

Courage in our hearts and energy to proceed.

United together, we shall achieve.

Nov 25, 2009

Positive Example to Bring Good Cheer to the Thanksgiving Holidays

As a med school student, we are constantly reminded that we know nothing. Perhaps this is to motivate us to stay awake during the wee hours of the night to learn the muscles involved that help us point our feet (plantarflexion) verses flexing our feet (dorsiflexion). In any case, being at the bottom makes us feel useless. Where are we supposed to direct our do-gooder energy in the two years we are stuck in the lecture halls?

Below is a great example of students making a positive impact on patient care. Are you a health professions student and want to make a positive impact? Join the "Check a Box. Save a Life." student campaign to improve the safety of surgery.

How Undergrads Make Doctors Wash Their Hands: "

Doctors and nurses don’t wash their hands as often as they’re supposed to. So we were interested to read about a program at UCLA Medical Center that managed to boost compliance with hand-washing guidelines from 50% to 93%, according to a paper published today in the journal Academic Medicine.

Doctors and nurses don’t wash their hands as often as they’re supposed to. So we were interested to read about a program at UCLA Medical Center that managed to boost compliance with hand-washing guidelines from 50% to 93%, according to a paper published today in the journal Academic Medicine.

The trick was getting undergrads to volunteer to come lurk in the hospital.

By the time the undergrad program launched about five years ago, UCLA had been trying to improve hand-washing adherence for a while, with mixed results. A program that enlisted nursing staff to conduct peer audits of hand washing led to reports of 100% compliance — despite the fact that “feedback from patients and their family members, as well as from the staff and physicians who had been patients, indicated that not all staff members adhered to the standards.”

About 20 students per year are selected for the undergrad program (described at length here), and they record 700 to 800 observations per month. They look for compliance with hand-washing guidelines, as well as adherence to rules for giving medication and handing-off a patient for surgery (adherence to those measures have improved sharply as well since the program launched).

It’s possible that hospital staff have simply learned to follow the rules when undergrad volunteers are looking over their shoulders. Still, it seems reasonable to infer that the gains measured by the undergrads is, at least to some extent, a reflection of an overall improvement. And the program is cheap — about 0.3 FTE during the first year of the program, which fell to 0.1 FTE by the fourth year.

Image: iStockphoto

Nov 21, 2009

What EpiPens Can Teach Us about Human Factors and Patient Safety

The first demo involved EpiPens, emergency treatment for individuals with severe allergies. Do you know how to use an EpiPen? It turns out, it's not very easy to learn, especially under the stress of saving someone's life! To simulate such an emergency situation, Dr. Gosbee asked us to "save his life" by reading the instructions and delivering the life saving dose of epinephrine correctly while holding our breath!

Read the full recap of our great speaker event, written by Chapter Leader Amy Silverstein, on the University of Michigan IHI Open School Blog!

Nov 9, 2009

A Grey’s Take on To Err is Human

Hi, my name is Eva and I watch Grey’s Anatomy.

I started about three years ago with the hotly anticipated Season 2 Finale and have been addicted ever since. I have tried to stop and had hoped that a change in environment (back in school and no TV) would stop this unhealthy habit. But, I have been unsuccessful. In fact, I believe I have reached a new level of addiction.

At the end of every episode I watch, I have been able to extract a lesson to justify my time spent following the lives of the characters at Seattle Grace Hospital. I tell myself that these lessons learned will help me become a better doctor…

For example, episode 6 of Season 6 ("I Saw What I Saw"), in my eyes, is a clear case study on patient safety and systems thinking. Let me explain.

- The system at Seattle Grace Hospital: The economy has shaken the foundations of Seattle Grace Hospital. Like leaders of hospitals around the country, the Chief of Surgery has had to make some tough decisions. A solution to some of the financial problems was a merger between Seattle Grace and Mercy West, a neighboring hospital. This led to staff cut-backs and an influx of new colleagues from Mercy West. The Mercy West additions were given no formal training to the ways of Seattle Grace. Caring for patients should be the same no matter where you are, right? Compounding this situation is the distrust and tension between the staff at Seattle Grace and the staff from Mercy West because they all anticipate more layoffs.

"Survival of the fittest" is everyone’s mentality. Everyone seeks to capitalize on the other’s weaknesses. In emergency situations, patients needing care are wheeled in and taken care of on a first come first serve basis. Patients are viewed as opportunities to shine. Everyone envies the surgical resident asked to assist on a patient with tough and difficult injuries. No one takes responsibility for the patients who don’t have “cool” conditions. The episode takes place just shortly after the merger of the two hospitals.

The case: Mrs. Becker and her son were just two of an influx of patients involved in a large fire at a hotel. Mrs. Becker presented with minor burns and her son appeared unscathed. Both Mrs. Becker and her son were very scared. After an initial hurried physical exam, Mrs. Becker and her son were left alone. She received treatment for her 2nd degree burns and morphine for her pain. By the end of the night, she suffered a pneumothorax (a collapsed lung) that was emergently treated with a cricothyrotomy, and then passed away due to respiratory distress followed by multiorgan failure. A disjointed “team” of seven residents (some of whose names many are still unfamiliar with) had attended to Mrs. Becker through the night.

The episode, filmed in the Rashomon style, retells the night from several vantage points to simulate the Chief of Surgery’s investigation on the death of Mrs. Becker. At the end of the interrogation, it was discovered that Dr. April Kepner had not completed Mrs. Becker's initial physical exam thoroughly. She missed the soot that had accumulated in Mrs. Becker's airway and lungs. The soot was the cause of Mrs. Becker's organ failure.

- Leadership actions taken: Dr. April Kepner was fired for her negligence.

We are very quickly approaching the 10th anniversary of the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) landmark patient safety report, To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. One of the most important messages of the report was that systems failures cause most injuries, not bad clinicians. Judging by the Chief's decision to fire Dr. April Kepner, he clearly has not read the report. Dr. Kepner was not a flawed or bad doctor, she was simply forced to operate in a bad system: She was not taught how to navigate the new hospital. She received no support from her colleagues. The process of admitting patients was chaotic and disorganized. Dr. Kepner and Mrs. Becker had no privacy. And communication between all of the physicians present was abysmal. Is it a surprise that Dr. Kepner would make such a simple mistake? I think it's a bigger surprise that more catastrophic mistakes didn't happen that day. Firing Dr. Kepner would not prevent a death like Mrs. Becker's death from happening again.

Dr. Shepherd has probably read To Err is Human. He understands that every system is designed to achieve the results that it gets. To prevent harm to patients, the Seattle Grace team needs to reduce the chaos and improve their work processes in order to fix the system. A point for those who swoon over Dr. McDreamy!

To have patient safety and systems thinking be major themes to an episode of a popular television show should be a good sign of progress in the field of quality improvement and patient safety, right?

Today's health care reform environment has thankfully showcased some of the many activities taking place at hospitals and professional societies to improve health care. Signs that quality improvement and patient safety are on the national radar have been allocation of funds in the Recovery Act towards comparative effectiveness research and reduction of hospital acquired infections. How to improve the quality of health care delivery while reducing costs has also reached the national scene (addressing overuse and underuse of health care). At a more local level, actions are being taken to reduce hospital acquired infections, reduce medication errors, and standardize safer and best practices (addressing misuse of health care). New accreditation standards and regulations such as no payment for "never events" adopted by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services can also be taken as a sign of progress.

But, do I feel safer or sense the improvements made whenever I interact with the health care system? As this episode of Grey's Anatomy demonstrates, tangible and measurable progress is probably still not yet within our grasp.

Once we get there, this episode should be rewritten. Seattle Grace will be a shining example of the transformation of the culture of medicine. All of the characters would not be individual heroes searching for glory, but would support each other in order to deliver better care for their patients. The Chief and hospital leadership would not bury mistakes like Mrs. Becker's death, but would take the time to identify root causes of the error and fix the system. And every single person would critically evaluate and make improvements to the complex work processes of delivering health care.

The best indicator of progress in "Grey's speak" would be a scene where Dr. Cristina Yang pouts because she was not named as the resident who discovered and made the greatest number of improvements in the Department of Surgery, rather than the fits we see her in now whenever she is not named the most technically accomplished surgical resident.

I should probably take a few seconds to look up the medical term for severe addiction now...

Nov 2, 2009

Join us at the IHI National Forum in December!

- Apply for a student or faculty scholarship (50-75% scholarships).

- Apply for a Student Travel Stipend ($250).

- Follow the Student Track to choose your sessions.

- Submit one of the three types of Student Posters.

- Join the Forum Students Facebook Group!

- Is this your first conference? Review Student Forum Survival Guide!

- Listen to the Student Audio Advice to hear what other students say about the Forum.

Oct 27, 2009

An Economics Lesson: Local Solutions

Because I now have less time to read things that don't look like textbooks and lecture notes, I've become a frequent podcast listener. Some of my favorite podcasts are This American Life, NPR's Fresh Air, IHI's podcast, and The 10th Wonder. I have about an eight minute walk to class, so a week of walking takes me through about two hour long podcasts!

After listening to two phenomenal This American Life podcasts coproduced by NPR's Planet Money team about the rising cost of health care, I've started listening to NPR's Planet Money podcast. One of the most recent NPR Planet Money podcasts is a short interview with Elinor Ostrom, the first woman to win the Nobel Prize for economics. The podcast describes her Nobel Prize winning work: qualifying the concept of The Tragedy of the Commons.

The Tragedy of the Commons is a famous economics dilemma about shared or common resources published in Science in 1968 by Garrett Hardin. The dilemma looks like this: a large group of people, hypothetically farmers, share a common resource, a pasture. No one owns the resource and each individual farmer, acting on self-interest, will use as much of the shared resource as possible. This leads to overuse and the ultimate destruction of the limited pasture. The tragedy of the situation is that everyone loses and everyone is stuck in this unfortunate situation. Any solutions to the problem must come from an outside source: government intervention or transforming the resource from a shared one to divided private ownership. Health care can also be seen as a Tragedy of the Commons situation.

Elinor Ostrom's work qualifies Hardin's original theory. In studying farmers in the Swiss Alps, she has found communities that have been able to maintain common properties for centuries by choice. Ostrom identified groups that used these shared resources as a community. In this example, the farmers share a common meadows pasture. The environmental driver for this shared resources model is that the meadows are "patchy." Unpredictably, some parts of the meadows would be lush and perfect for grazing, and at other times, those same parts would be covered with snow. Thus, it is in everyone's best interest to share the pasture. Over time, the community of farmers organized rules and regulations on their own...a local solution to a local problem, to regulate overgrazing and maintenance of the commons. These "rules" then became part of the local culture.

Here's where the "IHI bells" began to ring in my head! Reforming or transforming health care probably operates on the same principle. At the How Do They Do That? Low Cost, High Quality Health Care in America meeting in July of this past year, one of the big take home messages that I learned was that the solutions for low cost and high quality care were local, home-grown solutions. What worked in Temple, TX was the opposite of what worked in Sacramento. And Cedar Rapids was a bit of a hybrid of Temple and Sacramento. Operating under the guidelines of critical self-evaluation of their cost and health care outcomes, each hospital referral region (HRR), developed their own solutions. And over time, these practices became part of the local culture-- "that's just how they do things."

Ostrom believes that humans are complex: we do operate on principles of self-interest, but we are also able to act for the good of the group. The solutions to our common problems don't need to be imposed upon by an outside third party, they need to come from the community experiencing the collective problem. Perhaps the role of the third party would be to facilitate community problem solving by sharing success stories and making it easier for us to learn from each other.

As I work on the Check a Box. Save a Life. initiative, I see the need to emphasize that every group of health professions students hoping to promote, implement, and analyze safe surgical practices will be faced with their own unique set of challenges. How each group of students will get involved will be a local solution. But, I do hope everyone will share their experiences. We'll take a note from Ostrom's Nobel Prize winning economics work by following the examples of positive deviants and making local adaptations to our common problem.

Oct 24, 2009

and Take Off!

We want to provide you with some brief information about how to proceed following the launch:

- Please visit the IHI Open School website to view a recording of today's webcast:

- Coming this weekend to our website:

- http://www.safesurg.org/

student-mentors.html - "Check a Box. Save a Life." Pledge

- Online Sign-Up Sheet

- Detailed materials to help students:

- Spread awareness

- Promote Implementation of the checklist

- Collect data about checklist usage

- Suggestion box

Questions? email us at StudentSprint@gmail.com

Thank you again for joining us on this global student initiative and we look forward to hearing back from you soon.

- The Global Student Sprint Team

Oct 21, 2009

Transforming Leadership: From Individual Patients to the Community

About two weeks ago, I flew out to LA to take refuge from the Michigan cold. LA was unseasonably chilly, so I didn't quite get the sun and warmth that I had hoped for, but I got something better.

I attended the annual Asian Pacific Americans Medical Student Association (APAMSA) National Conference and spent my three days in LA meeting other medical school students and listening to inspiring lectures and workshops. The majority of the sessions focused specifically on health issues in the Asian American population. These include the incidence of Hepatitis B, the large number of uninsured in the Korean American community, the incidence of lung cancer, health awareness and education, and cultural competency.

California has a very large and diverse Asian population. I visited the Monterey Park/Freemont/Arcadia area on my last day in LA and could have sworn I was abroad! Because of this large Asian population, Asian American specific health issues are very apparent in California and there have been several great stories of progress. We had the privilege of hearing from Assemblywoman Fiona Ma of the San Francisco area and Assemblymember Mike Eng of the Los Angeles area describe the great strides that California has made in making the Hepatitis B issue a city-wide awareness and screening campaign (Hep B Free). We also heard from Dr. Jimmy Hara, Community Benefit Lead Physician for Kaiser Permanente Southern California, Dr. Arthur Chen, Medical Director of Alameda Alliance, Captain Cynthia Macri, M.D., Special Assistant of Diversity to the Chief of Naval Operations in the US Navy, and Dr. Paul Song, Director of Clinical Quality Improvement for Vantage Oncology who have all expanded their medical careers to address large scale efforts and discussions on how to better deliver health care, increase access, and shape national health policy. To top off this list of inspiring speakers and the many not mentioned here, our conference closed with talks from Dr. Sammy Lee, the first Asian American to win an Olympic gold medal for the US and Dr. Eliza Lo Chin, president-elect of the American Medical Women's Association.

Since most of these speakers hailed from California and have done such admirable work in the state of California, I felt a little discouraged at first. My hometown in South Florida's greatest health issues are geriatric and centered around ensuring that our seniors are able to live quality lives and obtain the health care that they need easily. My second home in Boston has nearly achieved universal health care access through its individual mandate, but now struggles to iron out the financial details of managing and continuing this initiative. And my new home in Ann Arbor? Unemployment is everywhere. I have yet to gain a better understanding of the health issues in Michigan, but my guess is that access is one of the top five concerns. With significantly smaller Asian communities in these three locales, how am I supposed to take the inspiring and encouraging words from the APAMSA conference and transform them into action locally?

The conference may have been for Asian Pacific American medical students, but the big themes of the conference were universal. The field of health care is changing as we speak and in order to prepare ourselves for the future we need to develop and transform our mindset and develop leadership skills. There are several junctions within a patient's pathway through the health care system that we as health professions students can act: from drug and medical devices development to care access to care delivery to care management. The one big thing that each of these areas of work have in common is expanding care from each individual patient, to care for a community and working with others as a team. I don't have to recreate the Hep B Free initiative in Ann Arbor. There are at least a million and one ways students can make an impact in health care. The safe surgery initiative: "Check a Box. Save a Life." is just one example (Tune into the launch tomorrow!).

As I think about transforming leadership and health care, here are a few considerations as illustrated by the Hep B Free initiative:

1) Get to know and understand your community, your team, and the "system" in which they operate and function.

Measure the burden of Hepatitis B in San Francisco, who this affects.

2) What do you want to accomplish?

Increase awareness about Hepatitis B, reduce the incidence of Hepatitis B, provide assistance to those who must manage Hepatitis B

3) How does that benefit your community and your team?

Decreased burden of disease and develop a replicable model for other cities to adopt

4) How do you develop support for your goal?

Involve community members, political figures, and anyone interested. This is a community effort that benefits the community, so the community itself should feel a sense of ownership for the initiative. To publicize the initiative and develop community support, the Hep B Free initiative hosted several dinner banquets at local restaurants with the understanding that "Asians bonded over food"

5) What kind of help do you need?

Medical support and expertise, community support, political clout, publicity, financial support

6) What's the plan and how will you execute it?

Launch educational messages to increase awareness, follow-up with health fairs that will provide screenings and vaccinations, provide information on how to manage Hepatitis B, train health professionals about Hepatitis B and how to help patients manage it.

7) How will you adapt to change?

Consistent feedback

8) How will you measure your progress?

Measure the number of people vaccinated, screened, trained, etc.

9) What kinds of improvements can be made?

Understand the best communication pathways: television/radio public service announcements, health fairs in conjunction with big holiday street fairs, transportation advertisements, how best to train health professionals, communication with public officials

10) How will you share your progress?

All materials are available on a website and direct support has been loaned to help Orange County launch a similar campaign

Don't be afraid to be creative and think out of the box! Also, words of advice from Dr. Dexter Louie, another great speaker at the conference, "Do what you can. We can't expect everyone to save the world quickly. Understand that whatever you do will be meaningful and will make a difference in the lives of others."

As I boarded the plane to head back to Ann Arbor, an idea popped into my head that I hope we as medical students can take ownership of to make positive change in our community. The Hep B Free initiative had developed lots of materials to educate their communities about Hepatitis B and the importance of getting screened and vaccinated. The area where they seemed to continue to struggle with was educating and training health professionals that would be caring for this newly informed community. Why should we wait till when physicians have begun practicing? Why not start the education process earlier?

Here at the University of Michigan, we have a curricular component called Longitudinal Cases. Every week, about ten of us meet in small groups led by a professor to discuss a case that is clinically relevant to the material we are learning in lecture. But, instead of focusing on the medicine of the case, we spend time discussing the sociocultural factors that may impact our interactions with the patient, how the patient interprets and manages the condition, etc. Understanding that our time in class is precious and that health concerns like Hepatitis B should be spread to all health professions students, why not develop a case study on Hepatitis B to be discussed in our Longitudinal Case sessions and make it a new standard addition to the curriculum? If we can make this happen, we will be expanding from individual patient care to caring for our community.

Oct 15, 2009

"It's kind of fun to do the impossible."

T - 7 DAYS TIL LAUNCH!!

The clock is ticking and we are amazed at how many students are joining us to be a part of this awesome global project! It gives us all the confidence that this will be an incredible success!

Everyday I am more and more amazed at how much fun working at the IHI and on this project has been!

The energy and excitement that we are getting back from students across the world, across all health professions underlines how we, students, are on our way to changing the quality of patient care.

Join us on the LIVE webcast on October 22nd and experience what I mean when I say

students are making the impossible, possible!

Let me again emphasize the word "FUN." The more we hear back from students wanting to take part in this, the more excited we get, and the more we want to spend time making this whole project a complete success!

We can't wait to join you all online and connect with each and every one of you who will have incredible energy and great ideas!

We'll chat soon!!!

- Shabnam

Join us on our Facebook page by clicking on the title of this post.

Oct 9, 2009

Check a Box. Save a Life.

Check a Box. Save a Life.

The 1st Global Student Sprint to Improve Healthcare.

Drs. Atul Gawande and Don Berwick will be addressing students on October 22nd at 12pm EST and encouraging them to engage in global efforts to improve the quality of patient care.

In effort to spread the incredible energy and enthusiasm of student involvement, we have gathered from all over the world at the IHI in Boston to get it underway...and we couldn't be more excited to be a part of the effort!

Oct 8, 2009

On Humans and Handles - Addendum

I wanted to expand on my previous point regarding the solitary design flaw in the office - the front exit door handle.

We've all seen the far side cartoon depicting the Midvale School for the Gifted (a classic!). I believe this cartoon derives its humor from two sources 1) Making the viewer feel superior, a theme of most jokes, and part of the funniest joke in the world (NB: As determined by scientists; British ones, to boot - sorry Andy), and 2) Reminding the viewer of a mistake that feels universal to the human condition.

How many times have you walked up to a door, attempted to pull it open, only to find that this was a "push" door? In my case, more times than I can count. Does this replay of the Midvale scene mean I’m, ahem, less than "gifted?"

In fact, no. The door handle problem represents a conflict between our automatic mental processes - the fast, decisive parts of our brains that allow us to catch a falling cell phone, or supply an effortless "you're welcome" when needed - and the slower, rational processes that think their way to an answer.

To the automatic brain, a vertical bar means “pull,” while the rational brain wonders, “don’t most exit doors push outward? Except in houses. Hmm. . . “ But by then, the mistake has been made.

An observer might laugh, but why? Isn’t it better to be frugal with one’s brainpower, committing it to loftier challenges than those presented by a handle? Even though I committed the mistake, it's not me who is wrong – it's the door.

To me, the push-pull problem is a favorite example of the predictability of human error. As with even the gravest medical mistakes, pulling the door is bound to make sense to someone on occasion. How do we prevent the embarrassment and wasted time resulting from door misuse?

We could put a sign up: "Note, push the door; thank you for your cooperation." We could penalize those who attempt to pull the door, and promote those who push it. We could host an annual seminar to remind everyone to always push the door (slogan: "be pushy about going home from work!"). We could even station an assistant (IHI Egress Coordinator) near the door to make sure we exited properly.

Or, we can admit that as long as humans are the ones grasping the handles, some will pull them, and try to fix all the world’s doors.

-Dan H.

Oct 5, 2009

People who work in glass offices. . .

At least is the case at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.

To set foot inside the IHI offices is to perceive, no doubt with dumbfounded expression in my case, what it means to truly practice what you preach. More on this in a moment (for those who absolutely can't wait - they have a virtual tour, of course. First, some background:

This week, I'm working with six friends - until yesterday, I might have written "other students interested in health care improvement," but a day of work and an evening on the town quickly cemented the upgrade - on a broad roll-out of the WHO Surgical Checklist to medical students worldwide.

To those new to the Checklist, it is a 19-item set of basic and essential safety questions which, when answered together by all members of a surgical team, ensures dramatic reductions in preventable harm. To be sure, the checklist succeeds, in part, like the pilot's checklists that inspired it's use. It guarantees that all required steps are taken to get patients (or passengers) through safely. I believe that the checklist is so effective because it also helps turn a group of coworkers into a true "team." That is, it makes clear the identities and roles of everyone in the operating room, raising the level of situational awareness. The gentleman resting peacefully on the table is not just the next patient to a scrub technician or medical student in the room, but rather, Mr. Jones, who is having his gallblader removed, and will probably do well throughout surgery but does have an allergy to Keflex. By investing every team member in the shared goal of safety, the Checklist produces lifesaving results. Impressive, considering it costs pennies to use.

Getting this piece of paper into the hands of every student who is or will one day be in an operating room - PA, RN, NP, MD, and PharmD, is our goal, and what brought me to the glass-lined, offices above the posh Charles Hotel, which house the idea factory known as the IHI.

The IHI offices are remarkable in many ways - the free diet coke certainly had one team member floored - mainly, because walking within them, you become absolutely sure that every element of their design has been both 1) planned, and 2) made better than a previous version at some point. There was one notable exception which bears mention, a design flaw on the front door handles, which I observed being - predictably - pulled rather than pushed by another of my teammates. A classic example in the science of human factors, perhaps the vertical door push is retained for its teaching value.

OK, back to the office. Amazing. Walking in, I Immediately noticed the IHI's mission and core values inscribed on the walls. "No needless deaths." A poignant motivator for everyone who passes by. High on the walls, one finds quotes from history's leaders in innovators: "Sometimes it's fun to do the impossible," or the more curt, "Hope is not a plan." Down the central corridor, the six aims of the IOM report, Crossing the Quality Chasm (report here, aims here) line the hallway's load-bearing posts - they are literally the pillars of the IHI!!

Another inspiring translation of mission into structure is visible in the offices - or, more correctly, invisible: The walls are all glass. Remember transparency, "going naked?" Well, the IHI is a place where you can see what everyone is doing at all times. There are no secret meetings here. Often, employees are walking into the otherwise unremarkable office shared by the CEO and COO and three others to grab a piece of candy. Nearly always, at least in my observation, they're smiling.

In its constant efforts to improve everything, its flat corporate culture, its and its conspicuous openness and transparency, the IHI is the epitome of the attitudes it seeks to impart to the health care professions. Visiting the IHI has been a revelation. This place is filled with an incredible energy and enthusiasm. This must be what it was like to be at Bell Labs in the 60s, or Google at the millenium. They even have a fun committee.

Practice what you preach, and please, preach often.

-Dan H.

Sep 25, 2009

Breaking News! Medical Students Shadowing Nurses

I just received this message from one of our Deans of Medical Education. Even though I have my first anatomy practical today, perhaps this is a sign that despite all of that, today will be a wonderful day!

Subject: New Required Educational Experience - Nurse Shadowing in M1 Year

Date: Sep 25, 2009 9:52 am

Message:

Dear M1 Class:

This year we are offering you a new required educational experience to complete during your M1 Year. You will each spend one half-day shadowing a nurse in the UM Health System.

Today’s health care delivery system challenges all health care professionals to provide care that is patient-centered, efficient, effective, safe, and timely. To meet this challenge, collaboration among members of health care teams (including, but certainly not limited to, physician and nurses) is vital. In at attempt to educate medical students on the role of nurses in the health care team as well as to foster open communication and teamwork between health professionals, this shadowing program – created originally by medical students – was run as a pilot last academic year. We hope that you enjoy the program as much as students last year did, and take something away that you can use for the rest of your careers as physicians.

We developed the following learning outcomes for the experience:

* Knowledge of what nurses bring to a health care team

* Ability to communicate effectively with a nurse

* Respect for the knowledge and skills of nurses

* Openness to learning about patient care from nurses

We will be asking you to complete a pre and a post-assessment of this experience. The post-assessment will serve as your documentation of completion of the required experience.

Sincerely,

Casey White, Ph.D., Assistant Dean for Medical Education

Little things like this that remind me why I decided to come to Michigan for med school! Do y'all have programs like this in your schools?

Sep 17, 2009

Quality Improvement in Baucus's Bill!

The bill provides for greater coverage of preventative care under Medicare, including providing a free yearly visit with a primary care physician for every beneficiary. There is some limited recognition of a primary care physician shortage. The bill will give PCPs a 10% Medicare payment bonus for five years.

The summary notes that a fee-for-service payment system is part of the problem, incentivizing more, not better, care. So, Baucus proposes various “value-based purchasing” schemes for Medicare to test. Under the hospital scheme, “a percentage of hospital payment would be tied to hospital performance on quality measures related to common and high‐cost conditions, such as cardiac, surgical and pneumonia care.”

There are also measures to promote greater coordination of care. It would “establish an Innovation Center at the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) that would have the authority to test new patient‐centered payment models that encourage evidence‐based, coordinated care. Payment reforms that are shown to improve quality and reduce costs could be expanded throughout the Medicare program.” It also directs CMS to track hospital readmission rates, and provides for financial rewards for those hospitals that keep readmissions low.

These measures are steps in the right direction—baby steps, perhaps, but they have legs. If CMS takes up the challenge they are being handed, and implements real quality metrics, this out-of-the-spotlight section of the bill could end up being incredibly significant. However, I do worry that these provisions may not be “safe” as the next round of negotiations go forward. They are threatened by rumors and fear mongering (we saw how end-of-life care counseling turned into “death panels”), and they are threatened by lawmakers who do not understand their importance. Baucus will have to demonstrate that these provisions are worth their costs; otherwise, they may not make it to the president’s desk. Let’s hope they do.

Sep 11, 2009

Obama's Reclamation of Health Care

But before I delve into the speech, I ought to introduce myself, as the newest contributor to the IHI Open School Blog. I’m a few months out of college and a few weeks into a one-year position here at IHI. My main interest in health care is about policy and politics, so my posts will follow the health care reform debate, as it relates to all of us who are working to improve the quality of the health care system and its delivery. Just as a note, I know my opinions can be rather assertive, so I want to be clear that I am writing for myself, as myself, not on behalf of IHI as an organization.

I’m starting from a few core assumptions. First, I assume health care is a human right. That means that any reform will be unacceptable to me if it does not achieve universal coverage. It also means that reform will be unacceptable if it leaves people “underinsured.” According to 2007 data from the Commonwealth Fund, about 25 million adult Americans are underinsured—their insurance fails to cover medical costs when tested by unforeseen diagnoses or accidents. Health insurance reform means making insurance more dependable, affordable, and transparent for all. Otherwise, health care is not a right but a luxury.

My second assumption is that government is not evil. Reform will go nowhere if any steps the government take are described as a Kafkaesque “government take-over.” Let’s be real, this is America…someone will always be there to make a profit from your pain. The reality is, government policy can change the incentives that doctors and hospitals face. The government can make it worth a doctor’s time to counsel patients on the medical decisions they must make. Government policy can reverse the perverse incentives that reward hospitals for expensive care. Most important, the government is the only publicly accountable body that can make such changes.

My third assumption is not really an assumption, but in fact a challenge to a commonly held one: that the free market is the answer to health care. A purely free market for health care would in fact be catastrophic. I’ll defer to Paul Krugman on this one (as I’m sure I’ll do on a lot of these posts):

There are two strongly distinctive aspects of health care. One is that you don’t know when or whether you’ll need care — but if you do, the care can be extremely expensive. The big bucks are in triple coronary bypass surgery, not routine visits to the doctor’s office; and very, very few people can afford to pay major medical costs out of pocket. This tells you right away that health care can’t be sold like bread. It must be largely paid for by some kind of insurance. And this in turn means that someone other than the patient ends up making decisions about what to buy…The second thing about health care is that it’s complicated, and you can’t rely on experience or comparison shopping. (“I hear they’ve got a real deal on stents over at St. Mary’s!”) (http://krugman.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/07/25/why-markets-cant-cure-healthcare/)

Getting back to the President’s speech, I really was very impressed that Obama rose to the challenge. He didn’t sound technocratic or boring, but he wasn’t vague or noncommittal on details either. He convinced me that the public option is not the crux of reform, and that it shouldn’t overshadow other critical consumer protections built into the law. He also chose some really great analogies to explain himself – I particularly liked how he said that a public option would provide greater choice and competition, just as public universities provide greater choice for and competition against private ones. You can read the full text here.

Some of the Republican’s reactions, though, absolutely disgusted me. I found myself screaming at the screen when Obama debunked the “death panels” lie, only for Republicans to remain seated as the rest of the audience jumped to its feet. It would have been consolation that their presence in the chamber was small--pushed to the back while Democrats took up more space than I’d ever seen--if I didn’t know that it was Democrats who have kept this reform from going forward in the past few months.

I loved the section to seniors, on Medicare: “So don't pay attention to those scary stories about how your benefits will be cut, especially since some of the same folks who are spreading these tall tales have fought against Medicare in the past and just this year supported a budget that would essentially have turned Medicare into a privatized voucher program. That will not happen on my watch. I will protect Medicare.” Another moment of uncomfortable Republican seatedness. And I loved the attempt to shame Congress for their inaction: “ We did not come to fear the future. We came here to shape it.”

Whether this speech can make a difference remains to be seen. I hope it can, and I’ll be watching closely to see.

Sep 8, 2009

My First Patient

However, this realization does not mean that I've never tried. The scars on my body are a road map to all of the ways that I have tried to figure out what lies beneath my skin. For example, I have a scar on my tongue from stapling it and messily extracting the staple on my own when I was six years old. My mom had just had surgery and I couldn't understand why she had staples across her belly. Weeks later, after I was told that doctors use instruments that look a little like kitchen knives to open and fix the body, I sliced my finger with the pizza cutter. Burning my cheek with my mom's curling iron not too long after the pizza cutter incident was the last straw. My parents very wisely remembered to add "don't try this" to any of their stories that could be interpreted as a new way to "test" something on myself. What I must have innately understood is that there is no better way to learn than to learn by doing.

With this dangerous streak of curiosity in me, I was surprised to find myself, 17 years later, walking with trepidation down the corridor towards the anatomy labs. The ultimate chance to learn was finally here. But, my steps had lost their usual spring (not just because my scrubs were too big) and rather than looking straight ahead, the scuff marks on the ground began to "fascinate" me. I couldn't contain myself when I thought about finally peeling away the skin to see how all of the different parts of our body worked together. Anatomy has a tangible tie to the practice of medicine, much more than sitting in a lecture hall learning about protein structure. So, what was I waiting for?

It wasn't the smell, the fear of cutting, becoming intimate with death, or even the overwhelming amount of material that was soon expected to become second nature to us. I was afraid of this gift: a complete stranger and her family have given me the opportunity to examine a body and know it far better than my own. The cadaver I was to spend the next few months with was not just going to be my teacher, but also my first patient. However, unlike my future patients, I will never know anything about her life except for what I can infer from her road map of scars. Her stories will remain a mystery. She has allowed me to crack open her spine, poke through her muscles, dig deep to find bundles of nerves--all things that she herself will never have the privilege of doing. Yet, her laugh, her voice, and the sparkle in her eyes are not even things that I can imagine and ascribe to her.

Perhaps it is this asymmetry of information that makes our relationship unique.While these missing pieces make it easier to objectively and academically canvass her body and focus on the science of the human body, I find myself inserting a piece of me into every gap of knowledge. For every incision I make and for every intricacy I am able to uncover, I am mentally making the same incision and discovery in myself. Her spinous processes are now also my spinous processes. Even though I have the exhilarating chance to remove each piece and uncover the delicate spinal cord, I must respect and care for each piece as if it were my own. I do my best to be attentive just in case I'm lucky enough to illuminate a precious pearl about her life.

After understanding and appreciating this special relationship with my first patient, I walk into anatomy lab with a sense of humbleness to accompany my geeky excitement. In anatomy, we are learning by doing. We are learning and practicing how to listen and learn from our patients by doing just that.

There really is no better way to learn.

The System- In the Patient's Words

My name is Jaclyn and I have been a lifelong resident of Connecticut and I’m a parent raising a special needs child. My daughter was born prematurely at UCONN Medical. In October 2003 my daughter was diagnosed with Cerebral Palsy and is currently wheelchair bound. For me, January 14th 2009 makes 6 years of being unemployed.

My daughter is totally dependent on me to carry her up and down the stairs for her baths and to be put to bed and to get her ready for school and other activities. She attends kindergarten and being that I don’t have ramps at either front or back doors, I have to roll her down the steps to get her on the bus. Her movements are so sporadic, I often will have random bruises such as a swollen lip from her hitting me in my face. I use to receive home health aid assistance 40 hrs a week and those were cut to 10 hrs a week, which is not efficient help for me caring for her. I don’t have any choices but to financially depend on state assistance and the disability I collect for my daughter. Although, under valid circumstances, I often feel degraded by the DSS workers. I have called nearly every daycare center/childcare provider in and around my town only to be told my daughter doesn’t qualify for daycare because she is a liability, she’s not potty trained or there is no qualified staff to take care of children like mine. I have called the senator who services my district, the mayor, the board of education, the United Way and spoke with the principle at her school to ask for help in finding a qualified daycare that will accept her. Those leads did not pan out and I finally given up when a coordinator at 211 info line explained to me that Connecticut doesn’t have daycares for special needs children.

I never wanted to quit my job but it was a disheartening sacrifice I had to make. If it were possible for me to work, I wouldn’t have anyone to place her on the bus or have anyone to receive her after school. The easy part is to go to work during the hours she is in school but quite often the school calls me to come pick her up because she may have had an accident or she’s not feeling well enough to stay. I also have to consider weather delays, shut downs, early dismissals and even her summer vacation.

Bottom line, I have virtually no assistance for my daughter or myself. My mother is the only one who will pitch in when she can but she is 64 years old and still working for herself. Placing my daughter in a group home would literally kill me. I love her more than I love myself and will fight and sacrifice for her till my last day.

Sep 2, 2009

Study: Surgeon Experience Doesn’t Impact Patient Deaths

Whether a trauma surgeon is a novice or experienced makes no difference on patients’ likelihood of survival, according to a recent study published in the Archives of Surgery. Instead, it appears that the overall system of care is more important.

Whether a trauma surgeon is a novice or experienced makes no difference on patients’ likelihood of survival, according to a recent study published in the Archives of Surgery. Instead, it appears that the overall system of care is more important.

We caught up with Elliott Haut, first author of the study and an assistant professor of surgery at Johns Hopkins, to discuss his findings. Here is an edited excerpt of the conversation.

Surgeons’ years of experience didn’t have an impact on patient mortality. Why is that?

I think there probably are very specific cases where very experienced surgeons do make a difference. But when you look at it as a whole — thousands and thousands of patients treated by different kinds of surgeons — it’s the system that makes the difference.

It doesn’t put [a veteran surgeon] out of a job. You need an experienced person to set up the system. It just means that we as a group of trauma surgeons need to have a system in place to treat all the patients in the same way, with evidence-based guidelines.

What defines the “structured program” that seems to be so important to patient outcomes?

At Johns Hopkins, we have a trauma attending surgeon. They’re going to show up with full team of residents. We have dozens of algorithms in our trauma manual that are given to our trauma residents. It helps guide you through some of the simpler things.

That senior, experienced trauma surgeon is an excellent mentor for junior people. We meet [as a trauma team] every morning at 7 a.m. We review every single trauma patient, go over what happened to them, what tests were done, vital signs, if the patient had surgery, what operation it was. It’s the real-time judgment and mentoring. All these pieces play a role; it’s not clear what’s the most important.

Aug 31, 2009

Simple Observations...

The lessons from one of the best hospitals in the world...: During the past month at MGH, arguably one of the best hospitals in the US, if not the world, I looked for subtle, innovative ideas that outsiders might not notice from simply taking a brief tour around the hospital. Health care is a complicated beast, and it really was the little things that made a big difference, not the obvious surgical robots or shiny buildings that meet the eyes of visitors.

1. The Get-to-know-me chart

In the room of every patient who cannot communicate for various reasons (stroke, delirium, intubation, whatever prevents a person from communicating), there was a Get-to-know-me chart, which consists of:

- Name AND 'Likes to be called'

- Important people in my life

- Favorites

- At home I use (patients check all that apply): glasses, contacts, hearing aids, dentures

- I understand information best when...

- Achievements

- Things that stress me

- Things that cheer me up

- Others

Some of these charts are filled by the patient before surgery expecting that they might not be able to communicate post-op. Others are filled by their family members. We can imagine how important these answers are when a patient is unable to communicate well with their providers, when they may only be conscious enough to respond to the names they are called everyday, when their world tumbles in times of sickness and the important people in their lives or things that usually cheer them up can make a huge difference, when they are thrown into a new environment and things you usually rely on to function (like hearing aids, glasses) are taken away.

2. The ED observation unit

It is the limbo between the ED and the floor. Many times ED patients await beds or lab results to determine whether they need to be admitted, at which time they no longer need the specific sets of skills and services from the ED staff. The ED observation unit houses these patients so that the ED can triage new patients that need urgent care.

3. Radiology consult

Any physician in the hospital can walk into radiology reading rooms (all of which are located in the same area: neuroradiology, CT, MRI) to review imaging of their patients with a radiologists in person, in order to ask field-specific questions that are usually not answered by the broad comments in the final read. Every time we walk in, the radiologists say with a smile, 'How can we help you?,' as if they were greeting customers. It is definitely a far cry from Elmhurst hospital, where you can't get a hold of radiologists at whom you need to yell and argue to have them approve the study that you want. Asking them for a personal imaging review would be asking for insults coming your way.

4. Location, location, location

At MGH, all microbiology labs (virology, parasitology, etc) are grouped together, next to the Infectious Disease offices and team rooms, and that is no accident. Whenever a test result is positive, the teams walk down the hall to review lab findings in person, ask questions and get rapid updates as soon as a culture turns positive. A neurosurgery ward is across the hall from the neuro SICU - crashing neurosurgical patients can be rapidly whisked across the hall to be stabilized in the ICU. The CCU is next to the cardiac step down unit - cardiac patients can move rapidly between the two units depending on their cardiac status.

5. The Bigelow service

In most hospitals, interns on a team split patients - one intern does not know anything (or care) about another intern's patients. On the Bigelow service, all the interns share all the patients on the floor. This requires the interns to communicate among themselves regarding all development and treatment choices for each patient. It fosters a foreign concept of teaching physicians to work together and communicate with one another regarding a shared patient, which above the intern level actually happens everyday and everywhere. It also makes sense that an intern knows all the patients on the floor, since all of them are only cared for by one intern on call each night.

6. Communication

On the consult service, I learned to uphold utmost politeness in communicating with other doctors. At the end of every consult we write - thank you for this interesting consult, we will follow along with you. We also make it a point to always communicate recommendations verbally to the primary team, ON TOP OF recommendations written in the chart. At Sinai, I inched gingerly up to the consulting team and before I could ask a question, their first comment was whether I had read the chart, as if we were meant to talk to one another through pieces of paper deprived of personal cues that enhance our grasp of a message.

7. The staff

Most of the hospital staff (nurses, in particular) were there for the grind to earn money - many took no interest in the medicine or in their patients. They clock out right at the end of their shift. Many refuse to do anything other than the required lab draws and vital checks - they refuse to assist others looking for information on the status of their patients, which arguably nurses know best. Others do not care to learn what the patient has and what treatments are coming their way. None of this is true at MGH - nurses ask to be present when doctors explain treatment plans to patients. They suggest care alternatives that improve patient outcomes or reduce costs.

MGH may have flaws that plague other hospitals across the nation (commercial-driven hospital policy, budget cuts in times of depression), but it has merits that sure make for a special place for the lucky patients that can afford it.

Aug 20, 2009

Teaching Patient-Centeredness

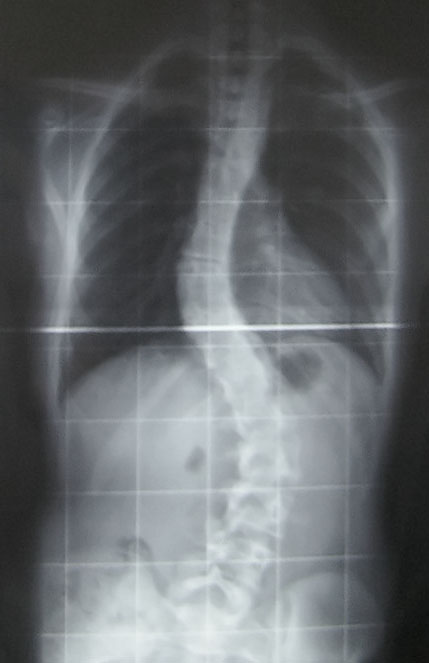

After quickly scanning my back, my physician said very nonchalantly, "This is easy, you have scoliosis."

I knew what scoliosis was. I remembered being screened throughout middle school by the school nurse and had always received a tap on my shoulder signaling that my spine was straight. My first question as I stared back at my doctor in disbelief was, "What does this mean?" Looking right past me, he explained scoliosis in very clinical terms, focusing on how the degree of the curve in my spine would greatly affect my prognosis. But, what I wanted to know was how this new word would change my life. What kind of new limitations would I have? Would I be able to run and play Ultimate Frisbee? And most importantly, would I be able to dance anymore?

His answer: "No, I wouldn't recommend you run or dance anymore." That was my coup de grâce. I was given a textbook to look at pictures of people with scoliosis and saw how the curves in their spine had caused gross displacments in their hips and rib-cages. I just couldn't imagine myself looking like that. What kind of changes were going to happen to me? What did I do to deserve this? My parents were right, I shouldn't have hunched over while studying. I walked out of the office in a stupor as my doctor told me we would just have to monitor the movement of my spine over time. If I felt any pain, I should just take some Advil.

As I walked home, I called my mom and told her the bad news. I was on the verge of tears. I just couldn't imagine my life with a completely different range of motion. I have been dancing since I was five years old and performing has become a significant part of who I am. This was a lot of information and emotion to swallow at once and I received no support from my doctor.

Thankfully, this was a misdiagnosis. I do not have scoliosis and I continue to run, leap, and spin through the weeks. I had sustained an injury that caused my hips to become misaligned and induce a twist in my lower spine. This caused an imbalance of muscle growth and pain--a common injury to dancers, according to the physical therapist. While the misdiagnosis had caused a week of emotional turmoil, it was the manner in which the diagnosis was given that made me feel lost, hopeless, and confused. In the doctor's eyes I was probably puzzle number 17 of the day and scoliosis was just another condition.

After just a few weeks of medical school, I'm already worrying about losing my ability to empathize with others and my future patients. During our first lecture, our professors told us that they were going to teach us the language of medicine. Will learning the language of medicine prevent me from speaking normally? Will I be as careless as my scoliosis doctor when speaking to my future patients?

Fortunately, the University of Michigan has a component of our curriculum to prevent this from happening. The program is called the Family Centered Experience. The first year medical students are grouped into pairs and each pair is assigned a patient and family managing at least one chronic disease. This could be a mother suffering from breast cancer, a father managing diabetes, or a grandfather suffering from a neurodegenerative disease. Throughout the year, we will be visiting our families and attending clinic visits with them in order to learn from the patient and their family what illness means and how it impacts the individual and family.

Yesterday, we met our families for the first time. Dr. Arno Kumagi, Director of the Family Centered Experience program, opened the evening's events with this basic framework. Doctors and patients view the problem or discomfort in two different perspectives. The physicians see the problem as a disease: the medical conceptualization of the process based on theories of pathophysiology. The conversations about disease are rooted in science, statistics, epidemiology, and pharmacology--all with their own specific terms and numbers. Patients see the problem as an illness: the subjective experience felt by the patient. The language of the patient is very human using words to describe feelings of loss, pain, discomfort, loneliness, alienation, and is based on language we use to communicate with other each other everyday.

Here is the example Dr. Kumagi used:

- Breast Cancer as a Disease: A malignant transformation of cells within the breast that is characterized by a lack of differentiation, invasiveness, and metastese to distant organs.

Breast Cancer as an Illness: A terrifying condition that may fundamentally threaten a woman's perspective of herself and her relationships with others, her health, her sexuality, her future plans, aspirations, and her very life itself.

The Family Centered Experience helps us nurture our sense of empathy and compassion. With patients and their families as our teachers, they will help guide us on our exploration on the meaning of illness, the doctor-patient relationship, and the ripple effect of illness and how it affects a family through their stories and experiences.

Third year medical school students have said that when we start seeing patients in the wards, we will always remember our Family Centered Experience volunteer families. We will see them and their experiences in our new patients. I cannot think of a better way to learn and experience patient-centered care. We not only get to hear the stories of our families, but for a short time, we get to experience illness with them too. I'm looking forward to my first home visit!

Do you all have similar program within your curriculum? How would you teach patient-centeredness? Can you think of any improvements to the Family Centered Experience program?

Aug 13, 2009

How Do They Do That? Low-Cost, High-Quality Care in America

Just yesterday, Atul Gawande, Don Berwick, Elliott Fisher, and Mark McClellan, published an Op-Ed in The New York Times. In the Op-Ed, the four weigh in on the current health care reform dialogue: raising taxes or rationing care in order to expand coverage and control the rising, nation-crippling health care costs. The take home message of the Op-Ed is that raising taxes or rationing care are not the only alternatives to achieving health reform. Why not try redesigning how health care is delivered so that it is both low-cost and high-quality?

This is the same situation as the misfits in middle school striving to be cool. What we as a nation need to do is identify these high-performing examples and ask, "How Do They Do That?"

This is an exploration that Atul Gawande, Don Berwick, Elliott Fisher, and Mark McClellan have already started. Data from The Dartmouth Atlas, a research initiative hosted by The Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice that uses Medicare claims data to document variations in how medical resources are distributed and used in the United States, was used to identify these high-performing examples. Out of the 306 Hospital Referral Regions (HRRs), regional health care markets for tertiary medical care, across the US, 74 high-performing regions were identified. (Click here to see the Medicare spending in your HRR). What does high-performing mean? These regions have per capita Medicare costs that are low or markedly declining in rank and have above average quality based on federal measures.

Out of these 74 high-performing HRRs, teams of hospital executives, physicians, and local leaders from 10 geographically different regions were invited to Washington, D.C., on July 21st to tell us, "How Do They Do That?" These HRRs included: Asheville, North Carolina; Cedar Rapids, Iowa; La Crosse, Wisconsin; Sacramento, California; Sayre, Pennsylvania; Portland, Maine; Everett, Washington; Temple, Texas; Richmond, Virginia; and Tallahassee, Florida.

The stories these 10 teams shared with us that day were truly remarkable. If the other 232 HRRs could perform like these high-performing examples, we'd be in good shape.

The most interesting finding of the day was that there is not just one way to become a high-performer. Some of these HRRs have one dominant health system where physicians are salaried (Scott and White Hospital and Clinic), while other HRRs had highly competitive systems sharing the market (Sacramento, CA).

Some of the major themes from the day were using data to inform change (The Op-Ed specifically refers to the number of CAT scans in Cedar Rapids), using lean/six sigma and other waste reduction/process improvement strategies in their daily operations, creating strong community ties and being accountable for the health of the region, training and creating opportunities for physician leadership, building a patient-centered culture, and continuous improvement. All of the HRR teams were surprised to find out that they were high-performers and acknowledge that they still have plenty of room for improvement.

Now that we've found these great examples, the cool kids of the health care middle school, we need to continue to ask, "How Do They Do That?" and follow their lead in redesigning health care to create a high-performing and healthy nation. Doesn't that sound like a great alternative?

Aug 8, 2009

The Journey Ahead...

Leaving is never easy. As I scroll through my iTunes library for musical inspiration, songs like NSYNC's "Tearin' Up My Heart", Ray Charles' "Georgia On My Mind", and The Sound of Music's "So Long, Farewell" pop out to describe how I feel. But, since I've never been a big fan of good-bye's, instead, I think the song "I've Had The Time of My Life" by Bill Medley and Jennifer Warnes popularized by the movie Dirty Dancing best encapsulates how I feel about my amazing year at IHI. So, Youtube the song and listen as you read! (Apologies to those who don't appreciate my cheesy-ness!)

No I never felt like this before

Yes I swear it's the truth

and I owe it all to you

Taking a leap of faith, I deferred from med school to work at IHI without fully understanding what IHI did on a daily basis, its role in the quality movement, or its impact on the world of health care. Fortunately, after a year, I now know the answers to those questions.

IHI's work aims to improve health care by applying operations management skills and tools to improve the efficiency, reliability, and effectiveness of health care delivery--viewing health care as a system. At the heart of all of this work is a strong commitment to make health care more patient-centered-- promoting patient safety and allowing the needs of the patient to drive the redesign of how health care professionals deliver care and how patients interact with the health care system. Most importantly, IHI aims to spread these changes and ideas to all. These activities include bundles to reduce hospital infections, lean and waste reduction skills, measuring and evaluating progress and improvement, learning how to work in teams across disciplines, and so much more. The content of IHI's work is truly impactful and fascinating, but is just one component of my amazing year.

Far more inspiring is the culture that IHI promotes locally within the office that not just propels us in our work, but also motivates all those in health care to continuously improve. IHI is an organization that "practices what it preaches". The culture in the IHI offices allows each individual to maximize his/her potential and relish in the energy and dynamism that teamwork provides. No one worries alone and like family, there is always at least one IHIer there to help when you need it. We work hard and we celebrate our successes. Best of all, every single person in the office is passionate about health care and their work. The enthusiasm is palpable and definitely flows freely around the boundariless office. If you ever need to feel inspired, take a walk around the office and you will be shocked with all that can be accomplished is a short amount of time. Remember that Surgical Safety Checklist Sprint? We asked hospitals to test the checklist in just 90 days! (Click here to see the map). I learned so much in my one year at IHI and feel so much pride to be a part of the IHI family. I didn't know what to expect when I started, and was given the world. Thank you to everyone at IHI for making my year memorable and life-changing!

My last few weeks at IHI were tough. All I could think about was inserting myself back into the broken health care system and how I could continue to cultivate those IHI values and skills while working hard to become a doctor. Would it be impossible for me to find opportunities to work with other health professions students? Would people find my IHI advocacy annoying? How will I find students interested in quality improvement? Do I even remember how to study? Was this going to be a really painful journey? While it has been extremely comforting to hear that the IHI doors will always be open for me, I knew I had jump out of the nest and test out my new wings.

Even though the incorporation of quality improvement and patient safety into health professions curricula has been slow moving, I have been very pleasantly surprised several times during my orientation week at the University of Michigan med school. My White Coat Ceremony did not emphasize the prestige of the medical profession, but rather the sacred gift we will now have to be a part of the lives of our patients. The Dean's address was focused on teamwork being integral to practicing medicine in the 21st century. We all spent time in the forests engaging in team building physical exercises that tested our ability to communicate effectively, pay attention to detail, and place our trust in each other. We've also already had two patient presentations where care that transcended across specialties and physical buildings was quintessential to positive patient experiences.

While I do already have hundreds of pages of reading, assignments to complete, and a quiz next week, I think I'm going to like it here. The University of Michigan also has an IHI Open School Chapter. So, I guess IHI will never be too far away. The journey ahead, I'm sure, will be...amazing.

Healthcare Reform and End-of-Life Costs

When President Obama's chief budget deputy Peter Orzag announced the stimulus bill (American Recovery and Reinvestment Act of 2009), he mentioned that the U.S. spends $700 billion each year on medical tests that don't help patients get healthier.

Policy analysts have long known that much of this seemingly wasteful spending occurs during emotionally challenging moments at the end of life. We often are willing to spend the most on those who are the sickest--even when it is unlikely to make them better. Given the highly sensitive situations involved, most politicians have been reluctant to touch this issue with a ten foot poll.

At least until now.

The recent healthcare bill drafted by the House takes on the costs of end-of-life care heads-on by providing doctors with financial incentives to counsel patients on creating "advanced directives" (commonly known as "Do Not Rescusitate/Do Not Intubate" orders). Since many patients can be sustained indefinitely on ICU life-support, the bill is meant to save money by reducing so-called "futile care".

However, the normally sympathetic editorial staff of the Washington Post has taken issue with this aspect of the bill, on the grounds that it is unethical to put financial rewards and end-of-life counseling in such close proximity.

What do you think? Join the conversation here or on Facebook

Aug 7, 2009

First, "The Cost Conundrum." Now what?

The article got noticed in high places. Peter Orszag, director of the White House Office of Management and Budget, blogged about it and concluded:

[I]n looking at an example like McAllen, Texas – a town where Medicare care costs have risen disproportionately relative to national and local benchmarks, and very quickly – it is hard not to ask what our return is on this high-taxpayer investment. From what we can measure, it’s not better health. It is simply more care.

Upon reading Gawande's article, I remember thinking, "Things must be feeling grim over in McAllen today." I felt a little sorry for them. McAllen happens to be among the most expensive health care markets in the U.S., and it's easy (and of course, instructive) to point the finger at wasteful practices there. But I wondered: do articles like this actually prompt other hospital chiefs to examine their own spending? Or does everyone shake their head at the sad state of affairs in McAllen and then continue doing things exactly the same way they've always been done?

Today I came across a really interesting blog post that (in part) answered this question for me. The post describes a memo that an unnamed hospitalist physician sent his residents, using Dartmouth Atlas data to compare the cost of care at their hospital to that of two others. The comparison, let us say, was not favorable. Here's how the physician ended his memo:

We are at the top 1% in terms of cost intensity and we use a hell of a lot of specialists...

Bottom line: When it is time for hospitals to take a haircut, even taking into account higher spending in our area -- and this is a reality as well -- we are still inefficient by the gobful. Trust me, people that matter are watching and they know we can do a lot better. Something to keep in mind as we think about how to practice sensibly. More does not equal better and it is only a matter of time before we are requested to step up and get out our `A' game. The folks who will be asking, by the way, won't be bringing cookies.

Here's what I take away from all this:1. That is one awesome teacher. All teachers should be that honest with their students.

2. Local health care spending (whether it's especially high or especially low) is about to come under some serious scrutiny. From people like Peter Orszag, and people like Orszag's boss.

3. The people doing the scrutinizing will be relying in part on the Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care, which '"documents glaring variations in how medical resources are distributed and used in the United States."

Anyone can use the Dartmouth Atlas to look up how their state, town, or hospital is doing when it comes to using care efficiently. Is your hospital a big spender? And if so, who's working on fixing that? Go find out. Because people are going to be asking about it, and they won't be bringing cookies.