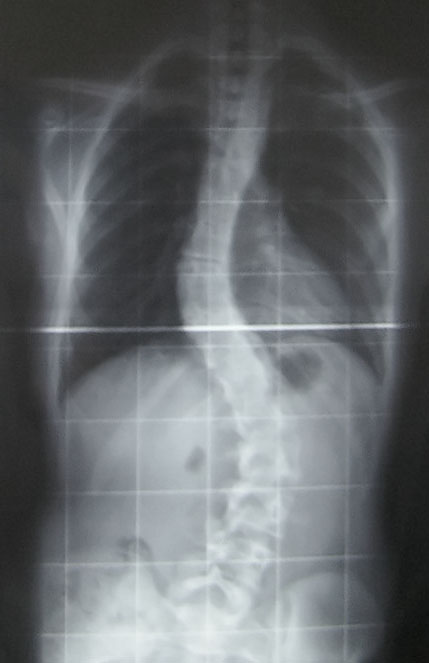

After quickly scanning my back, my physician said very nonchalantly, "This is easy, you have scoliosis."

I knew what scoliosis was. I remembered being screened throughout middle school by the school nurse and had always received a tap on my shoulder signaling that my spine was straight. My first question as I stared back at my doctor in disbelief was, "What does this mean?" Looking right past me, he explained scoliosis in very clinical terms, focusing on how the degree of the curve in my spine would greatly affect my prognosis. But, what I wanted to know was how this new word would change my life. What kind of new limitations would I have? Would I be able to run and play Ultimate Frisbee? And most importantly, would I be able to dance anymore?

His answer: "No, I wouldn't recommend you run or dance anymore." That was my coup de grâce. I was given a textbook to look at pictures of people with scoliosis and saw how the curves in their spine had caused gross displacments in their hips and rib-cages. I just couldn't imagine myself looking like that. What kind of changes were going to happen to me? What did I do to deserve this? My parents were right, I shouldn't have hunched over while studying. I walked out of the office in a stupor as my doctor told me we would just have to monitor the movement of my spine over time. If I felt any pain, I should just take some Advil.

As I walked home, I called my mom and told her the bad news. I was on the verge of tears. I just couldn't imagine my life with a completely different range of motion. I have been dancing since I was five years old and performing has become a significant part of who I am. This was a lot of information and emotion to swallow at once and I received no support from my doctor.

Thankfully, this was a misdiagnosis. I do not have scoliosis and I continue to run, leap, and spin through the weeks. I had sustained an injury that caused my hips to become misaligned and induce a twist in my lower spine. This caused an imbalance of muscle growth and pain--a common injury to dancers, according to the physical therapist. While the misdiagnosis had caused a week of emotional turmoil, it was the manner in which the diagnosis was given that made me feel lost, hopeless, and confused. In the doctor's eyes I was probably puzzle number 17 of the day and scoliosis was just another condition.

After just a few weeks of medical school, I'm already worrying about losing my ability to empathize with others and my future patients. During our first lecture, our professors told us that they were going to teach us the language of medicine. Will learning the language of medicine prevent me from speaking normally? Will I be as careless as my scoliosis doctor when speaking to my future patients?

Fortunately, the University of Michigan has a component of our curriculum to prevent this from happening. The program is called the Family Centered Experience. The first year medical students are grouped into pairs and each pair is assigned a patient and family managing at least one chronic disease. This could be a mother suffering from breast cancer, a father managing diabetes, or a grandfather suffering from a neurodegenerative disease. Throughout the year, we will be visiting our families and attending clinic visits with them in order to learn from the patient and their family what illness means and how it impacts the individual and family.

Yesterday, we met our families for the first time. Dr. Arno Kumagi, Director of the Family Centered Experience program, opened the evening's events with this basic framework. Doctors and patients view the problem or discomfort in two different perspectives. The physicians see the problem as a disease: the medical conceptualization of the process based on theories of pathophysiology. The conversations about disease are rooted in science, statistics, epidemiology, and pharmacology--all with their own specific terms and numbers. Patients see the problem as an illness: the subjective experience felt by the patient. The language of the patient is very human using words to describe feelings of loss, pain, discomfort, loneliness, alienation, and is based on language we use to communicate with other each other everyday.

Here is the example Dr. Kumagi used:

- Breast Cancer as a Disease: A malignant transformation of cells within the breast that is characterized by a lack of differentiation, invasiveness, and metastese to distant organs.

Breast Cancer as an Illness: A terrifying condition that may fundamentally threaten a woman's perspective of herself and her relationships with others, her health, her sexuality, her future plans, aspirations, and her very life itself.

The Family Centered Experience helps us nurture our sense of empathy and compassion. With patients and their families as our teachers, they will help guide us on our exploration on the meaning of illness, the doctor-patient relationship, and the ripple effect of illness and how it affects a family through their stories and experiences.

Third year medical school students have said that when we start seeing patients in the wards, we will always remember our Family Centered Experience volunteer families. We will see them and their experiences in our new patients. I cannot think of a better way to learn and experience patient-centered care. We not only get to hear the stories of our families, but for a short time, we get to experience illness with them too. I'm looking forward to my first home visit!

Do you all have similar program within your curriculum? How would you teach patient-centeredness? Can you think of any improvements to the Family Centered Experience program?